Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is an important concept in Physics that studies how atomic nuclei behave when placed in a magnetic field and exposed to radiofrequency waves. It helps in understanding the magnetic properties of nuclei and has wide applications in medical imaging (MRI) and material analysis.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is a spectroscopic technique that measures the interaction of nuclear spins with an external magnetic field and radiofrequency (RF) waves.

Fundamental Principles of NMR

Nuclear Spin:

- Just like electrons, protons, and neutrons inside the nucleus possess a quantum property called spin (Intrinsic angular momentum).

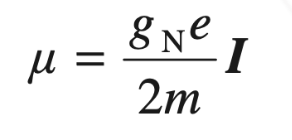

- Nuclei with non-zero spin behave like tiny magnets, with an associated magnetic moment (μ).

- The magnetic moment is directly proportional to the nuclear spin quantum number.

Interaction with an External Magnetic Field

- The magnetic moment interacts with the magnetic field to produce energy states corresponding to different alignments. When placed in a magnetic field, the nucleus can align:

- Parallel (lower energy state) — alignment with the magnetic field.

- Antiparallel (higher energy state) — alignment opposite to the magnetic field.

- There is a slight population difference between these two states, creating a net magnetization.

Magnetic resonance

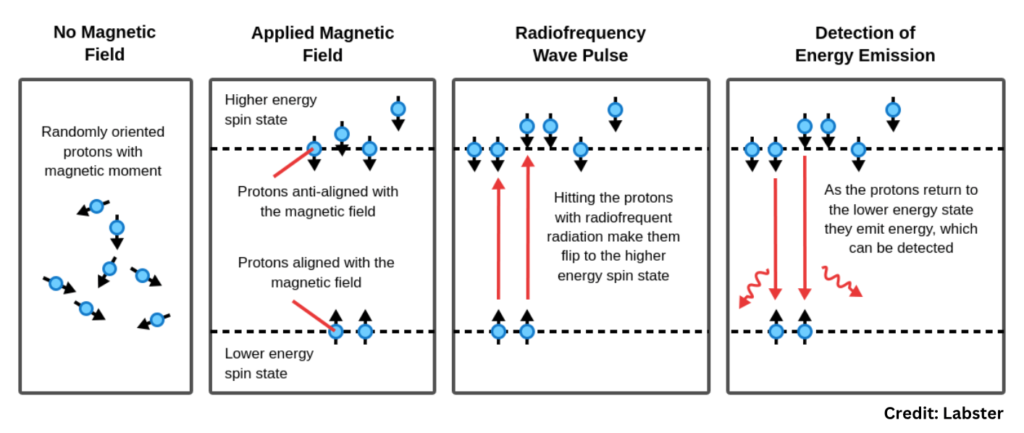

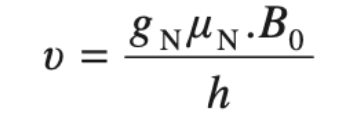

- The energy difference between these states is crucial for resonance to occur. The nuclei absorb energy when exposed to a radiofrequency (RFRF) that matches their Larmor frequency.

- The absorbed energy causes nuclei to flip from the low-energy state to the high-energy state. (+1/2↔−1/2). This transition is commonly referred to as a ‘spin flip’.

- ΔE: Energy difference between the two spin states.

- γ: Gyromagnetic ratio (a nucleus-specific constant).

- ℏ: Reduced Planck’s constant.

Relaxation Processes

- Once the RF pulse is turned off, the nuclei relax back to their lower energy state, emitting RF radiation.

- The emitted RF signals (free induction decay or FID) from the nuclei are detected using a receiver coil.

- Using a Fourier Transform, these signals are processed into a spectrum or image.

Relaxation Mechanisms:

- After excitation, the nuclei return to their equilibrium state through two processes:

- T1 Relaxation (Longitudinal Relaxation): Energy exchange with the surroundings (lattice).

- T2 Relaxation (Transverse Relaxation): Dephasing of spinning nuclei due to local magnetic field interactions.

- The relaxation times (T1 and T2) provide critical information about the sample’s environment.

Steps in NMR Spectroscopy

- Sample Preparation: The sample is placed in a magnetic field inside the NMR machine.

- Magnetic Alignment: The nuclei align with the magnetic field.

- RF Excitation: A specific RF pulse is applied to excite the nuclei.

- Signal Emission: As nuclei relax, they emit RF signals that are captured by detectors.

- Data Analysis: The signals are processed into a spectrum, revealing molecular structures and properties.

Spin Quantum Number:

- The spin of a particle is characterized by a quantum number denoted as I, the nuclear spin quantum number.

- The spin quantum number (I) determines the number of possible orientations of the nucleus in a magnetic field.

[Quantisation → (2I + 1) orientations]

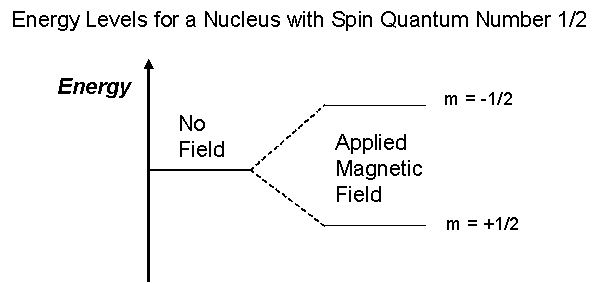

- I=1/2 (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C): Two energy levels (+1/2, −1/2).

- I=1 (e.g., ²H): Three energy levels.

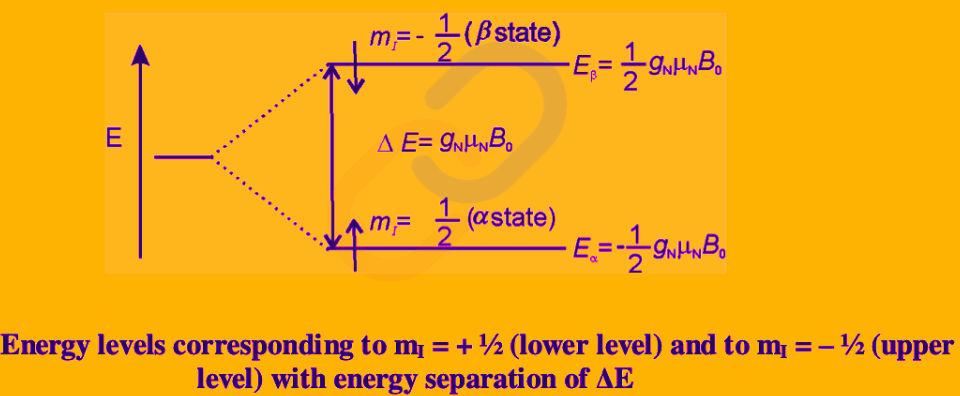

Example: The energy levels for I = 1⁄2 nuclei are given as

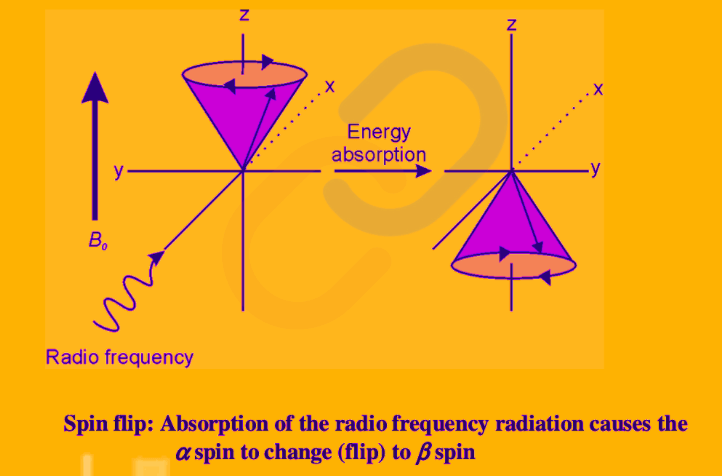

Traditionally, the energy level (or state, as it is commonly called) with m= 1⁄2 is denoted as α and is sometimes described as ‘spin up’ and the state with m = − 1⁄2 is denoted as β and is described as ‘spin down’.

Spin Flip: A suitable radiofrequency radiation can bring about the transition from the α to β spin state.

Larmor Precession

A spinning nucleus under the presence of an external magnetic field can precess around the axis of an external magnetic field in two ways; it can either align with the field (low energy state) or it can oppose the field direction (high energy state).

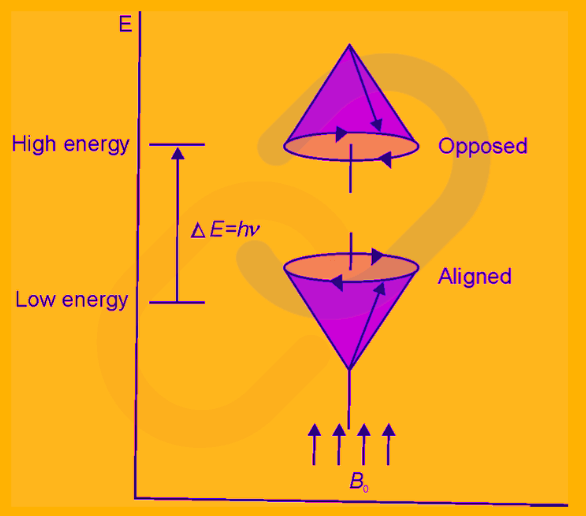

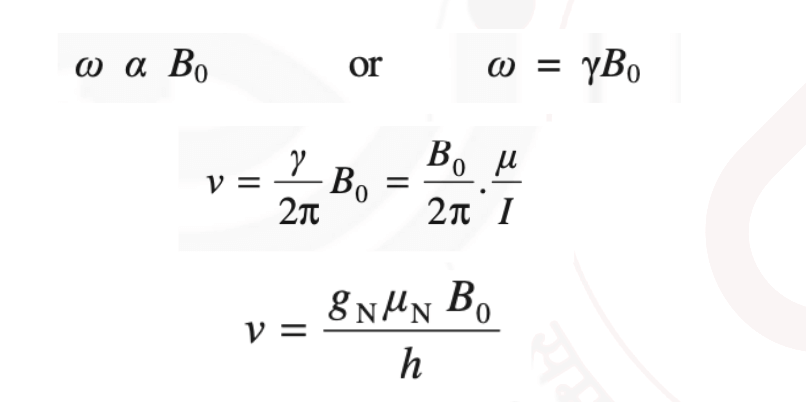

Larmor Frequency: The frequency at which the magnetic moment “precesses” around the magnetic field is called the Larmor frequency. It is given by:

Therefore, the precessional frequency of the spinning nucleus is exactly equal to the frequency of electromagnetic radiation necessary to induce a transition from one nuclear spin state to another spin state.

Example: In a magnetic field of 1 Tesla, the resonance frequency for hydrogen nuclei (¹H) is approximately 42.58 MHz.

NMR-Active Nuclei

- Non-Zero I: NMR-active nuclei are those with a non-zero nuclear spin (I). These nuclei have odd numbers of protons and/or neutrons.

- Common NMR-active nuclei include:

- Protons (1H): Most commonly used in NMR due to its abundance and sensitivity.

- Carbon-13 (13C): Used in carbon-13 NMR, especially for organic compound analysis.

- Other nuclei: Such as nitrogen-15 (15N), phosphorus-31 (31P), and fluorine-19 (19F), among others.

NMR-inactive Nuclei

- Zero I: Nuclei with zero spin (e.g., carbon-12, 12C – even number of protons and neutrons) do not have a magnetic moment and are NMR-inactive. These nuclei cannot be detected directly using NMR.

Factors Affecting NMR

- Magnetic Field Strength: Higher field strengths lead to better resolution and sharper peaks.

- Temperature: Temperature can affect the molecular motions and therefore the NMR signals.

- Chemical Environment (Chemical Shifts) : Nuclei in different chemical environments experience different magnetic fields, causing a shift in the resonance frequency.

- Coupling: Spin-spin interactions split peaks into multiplets.

- Concentration: High concentration increases the intensity of peaks but can also lead to peak broadening due to overlapping signals.

- Limited Sensitivity for Low-Abundance Nuclei: NMR sensitivity for certain nuclei (such as Carbon-13 or Nitrogen-15) can be low, requiring larger sample amounts or longer scanning times.

- Relaxation Times (T₁ and T₂)

- Short T₂ values lead to broader peaks (less resolution).

- Long T₂ values allow for narrower peaks and better resolution.

Applications of NMR

1. Chemistry

- Molecular Structure Elucidation: By analyzing the chemical shifts, spin-spin coupling, and integration in an NMR spectrum, scientists can determine molecular connectivity and functional groups.

- ¹H NMR (Proton NMR) helps identify hydrogen environments in molecules.

- ¹³C NMR (Carbon-13 NMR) is used to map the carbon skeleton of compounds.

- 2D and 3D NMR techniques (such as COSY, NOESY, HSQC) provide further details about atomic connectivity and spatial relationships.

- Quantitative Analysis: NMR can be used to quantify the amount of a specific compound in a mixture by comparing the integration of signals.

- Reaction Monitoring: NMR can be used to monitor chemical reactions in real-time by tracking the changes in the chemical shifts of reactants and products.

2.Biochemistry

- Protein Structure Analysis: NMR is used to determine the 3D structures of proteins, enzymes, and nucleic acids in solution.

- Metabolomics: NMR helps in profiling metabolites in biological samples like blood, urine, or tissues.

- Example: Studying metabolic changes in diseases like diabetes or cancer.

3. Pharmaceuticals

- Drug Design and Development:

- NMR is used to study the interactions between drug candidates (ligands) and their targets (receptors, enzymes).

- Quality Control:Used to verify the purity and composition of drugs.

4. Food and Agricultural Sciences

- Food Quality Control: NMR is used for the analysis of food composition, including determining the concentration of fats, sugars, and proteins.

- Used for authenticity testing (e.g., detecting adulteration in honey, oils, and milk).

- Quantifies water content, pH levels, and other ingredients.

- Plant Metabolomics: Helps in the analysis of plant metabolites for agricultural research, improving crop yield, resistance, and nutritional quality.

- Energy Sector: Understanding fuel composition and developing biofuels.

5. Material Science and Chemistry

- Polymers and Plastics:

- Analyzing the molecular structure and dynamics of polymers to determine properties like flexibility, strength, and durability.

- Example: Characterizing the structure of polyethylene or rubber.

- Nanomaterials:

- Studying the interaction between nanoparticles and surrounding materials.

- Example: Investigating the properties of carbon nanotubes or graphene.

- Solid-State NMR: This application is used to study the structure and properties of solids (e.g., catalysts, ceramics, and battery materials).

6. Clinical and Medical Applications

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is a clinical imaging technique derived from NMR principles. It uses ¹H NMR signals to produce detailed images of tissues, helping diagnose conditions like cancer, neurological diseases, and musculoskeletal disorders.

- In Vivo NMR: NMR can be used to study living organisms (in vivo) to analyze metabolic pathways, neurotransmitter levels, and other physiological processes in real-time.

- Bone Density and Mineral Studies: NMR is also used to analyze mineral compositions in bones and other biological tissues for detecting diseases like osteoporosis.

7. Geology and Environmental Studies

- Pollution Monitoring: NMR is used to study and monitor environmental pollutants such as pesticides, plastics, and other chemicals.

- Water Quality Analysis: NMR helps analyze the chemical properties of water, such as identifying dissolved organic compounds, salts, and contaminants.

- Example: Detecting microplastics in water using NMR spectroscopy.

- Petroleum Exploration: NMR is used to study rock samples to determine porosity, permeability, and fluid content.

- Example: Analyzing shale rock formations for oil and gas reserves.

8. Forensic ScienceForensic Chemistry:

- NMR can be applied in forensic investigations to identify substances found at crime scenes, such as drugs, poisons, and explosives.

- Helps in the analysis of blood, hair, and other biological samples for identifying compounds or toxins.

Advantages of NMR

- Non-destructive: Preserves the sample for future analysis. This is crucial for precious or rare samples, such as biological tissues, archaeological artifacts, or precious chemicals.

- High sensitivity and resolution: It offers excellent resolution, enabling researchers to distinguish even closely spaced signals.

- Direct structural determination: Unlike X-ray crystallography, which requires the formation of large, high-quality crystals, NMR can work with samples in solution or even in solid form

- Quantitative: Allows precise concentration measurements without calibration.

- Can analyze complex mixtures: No need for separation of components.

- Dynamic information: NMR is capable of studying molecular motions, including protein folding, ligand binding, and diffusion properties.

- Multi-dimensional techniques: Modern NMR techniques like 2D, 3D, and even 4D NMR enable deep structural and functional insights.

- Non-invasive in medical applications: Used in MRI and in vivo studies.