Concept of Charge In Physics is a fundamental property of matter that gives rise to electric forces and interactions. It exists in two types, positive and negative, and plays a vital role in understanding electricity and magnetism.

Previous year Questions

| Year | Question | Marks |

| 2016 | Two identical metallic spheres A and B of exactly equal mass are taken. If A is charged with Q positive charge and B is charged with Q negative charge, then which sphere will be heavier after charging and why ? | 2M |

| 2016 Special exam | Distinguish between conductor, semi-conductor and insulator on the basis of band theory solid. | 10M |

Concept of Charge

Electric charge is the basic unit of electricity and is responsible for electrical interactions in nature.

History:

- The concept of electric charge dates back to 600 BC, when the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus observed that amber rubbed with wool or silk could attract light objects like straw and paper. This led to the discovery of electrification by friction and the birth of electrostatics.

The Origin of the Term “Electricity”

- The word “electricity” comes from the Greek word “elektron,” meaning amber—the first substance observed to exhibit electrical effects.

Definition: Charge is an intrinsic property of subatomic particles (such as electrons and protons) that determines how they interact with electric and magnetic fields.

- Unit of Charge: Coulomb (C)

- Symbol of Charge: q or Q

- Charge of an Electron: – 1.6 × 10⁻¹⁹ C

- Charge of a Proton: +1.6 × 10⁻¹⁹ C

Types of Charge

- There are two types of electric charge: Through years of careful study, scientists realized that there are only two kinds of charge, which were later named positive and negative by Benjamin Franklin.

- Positive Charge (+) – Carried by protons

- Negative Charge (-) – Carried by electrons

- Neutrons have no charge (neutral). Atoms are normally neutral because they have an equal number of protons and electrons.

- Objects become charged when they gain or lose electrons, leading to either positive or negative charge.

Properties of Electric Charge

1. Like Charges Repel, Opposite Charges Attract

- Two positive charges (+ +) repel.

- Two negative charges (- -) repel.

- Opposite charges (+ -) attract each other.

2. Additivity of Charges

- Electric charge behaves like a scalar quantity, meaning it can be added algebraically.

- Mathematically, for a system with n charges q1,q2,q3,…,qn , the total charge is:

Qtotal=q1 + q2 + q3 +….+ qn

3. Charge is Conserved

- The total charge in an isolated system remains constant.

- Charge cannot be created or destroyed, only transferred.

Subatomic Conservation of Charge

- Charge conservation also holds at the particle level.

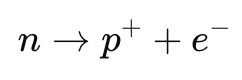

- A neutron can decay into a proton and an electron, as in:

- The total charge before and after decay remains zero.

4. Charge is Quantized

- Charge always exists in discrete packets and is an integral multiple of a fundamental unit of charge.

- This smallest possible charge is denoted by e, which is the charge of an electron or proton.

Q = ne

where n is an integer (positive or negative), and e=1.602×10-19 C

- A body can have charges like ±e, ±2e, ±3e, but never 1.5e or 2.7e.

Experimental Confirmation of Charge Quantisation

- Faraday’s Laws of Electrolysis first suggested charge comes in discrete packets.

- Millikan’s Oil Drop Experiment (1912) provided direct experimental proof that charge is always a multiple of e.

5. Charge is Transferable

- Electrons can move from one body to another, creating charge imbalance.

- Example: Rubbing a balloon on hair transfers electrons, making the balloon negatively charged.

6. Charge is Invariant

- The charge of a particle remains the same regardless of motion or frame of reference.

Measurement of Electric Charge

- In the SI system, electric charge is measured in Coulombs (C).

- One Coulomb (1 C) is defined as:

- The charge flowing through a wire in 1 second if the current is 1 Ampere (A).

- That is,1C=1A⋅1s

- Magnitude of Elementary Charge (e):

e=1.602×10-19 C

- Since 1 Coulomb is a very large charge, we often use smaller units:

- 1 microcoulomb (µC) = 10-6C

- 1 millicoulomb (mC) = 10-3 C

- Example: 1 Coulomb of charge is approximately equal to the charge of 6.25×1018 electrons.

Read more…

FAQ (Previous year questions)

According to the band theory of solids, the electrical properties of materials depend on the arrangement and energy gap between the valence band (occupied by electrons) and the conduction band (where electrons can move freely to conduct electricity).

Property

Conductor

Semiconductor

Insulator

Valence Band

Partially filled or overlaps with conduction band

Completely filled

Completely filled

Conduction Band

Partially filled

Empty at 0 K; partially filled at room temperature

Completely empty

Band Gap

Zero or negligible

Small (~1 eV)

Large (>3 eV)

Energy Required for Conduction

Almost none

Small thermal or light energy

Very high energy required

Availability of Free Electrons

High

Moderate (temperature dependent)

Very few or none

Electron Movement

Free electrons available

Limited electrons excited thermally

Electrons do not move freely

Electrical Conductivity

Very high

Moderate

Very low/negligible

Effect of Temperature

Conductivity decreases slightly

Conductivity increases significantly

No significant effect

Examples

Copper, Silver, Aluminium

Silicon, Germanium

Glass, Rubber, Plastic

Use in Devices

Wiring, electrical conductors

Diodes, transistors, solar cells

Insulation in circuits

Band theory effectively explains why materials behave differently under electrical fields. Conductors allow free flow of electrons, semiconductors allow controlled flow, while insulators resist electrical conduction due to a large energy gap.

Electrons have a mass, and this mass is non-negligible when comparing the masses of charged and uncharged objects.

A negative charge on an object means it has gained electrons, and a positive charge means it has lost electrons.

Sphere B gains mass, while sphere A loses mass.

Therefore, the mass of sphere B will be greater than the mass of sphere A after charging.

Sphere B will be heavier after charging. Sphere A loses electrons, reducing its mass, while sphere B gains electrons, increasing its mass.