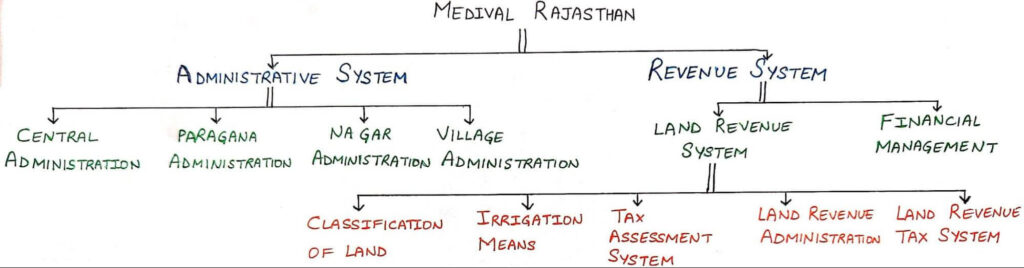

Medieval Administrative and Revenue System in the context of Rajasthan History reflects the structured governance and taxation practices of that era. It included the Central, Village, and District Administration systems, all functioning under the influence of the Feudal System. Key aspects of revenue collection involved Major Taxes and the Lag-Bag system, which formed the backbone of the region’s economic administration.

Medieval Administrative and Revenue system

When the Rajput rulers came into contact with the Mughals, they became familiar with the Mughal administrative system. Gradually, this system began influencing the governance of Rajasthan’s states. During Maharaja Rai Singh’s rule in Bikaner (1574–1612 CE) and Maharaja Sur Singh’s reign in Marwar (1595–1619 CE) as well as during Maharana Amar Singh-I’s rule in Mewar (1597–1620 CE), who signed a treaty with the Mughals in 1615 CE, the administration of Rajputana states was reorganized based on the Mughal model.

Administrative System

Central Administrative System

The ruling class in Rajasthan comprised independent rulers who governed their states with complete sovereignty. They held titles such as Maharajadhiraj and Rajarajeshwar, symbolizing their supreme authority. The ruler was responsible for governance, military leadership, justice, forming treaties, and maintaining state security. They enjoyed special privileges like holding court sessions, organizing royal processions, and awarding titles. The responsibility of protecting the state earned them the honorific Khumman. Queens often took charge of governance during the ruler’s absence or minority. To assist the ruler;

Council of Ministers :

- Members of this council, appointed by the ruler, either hereditarily or from outside the royal family, handled various state functions. For instance according to Sarneshwar inscription in Mewar CoM included :

- Akshapatalik managed records and archives.

- Sandhivigrahik oversaw war and peace.

- Amatya acted as the chief minister.

- Bhisgadhiraj served as the chief physician.

The Prime Minister (Pradhan) :

- He played a pivotal role in administrative, military, and judicial matters. This position was equivalent to a modern-day chief minister and was known by various titles in different regions, such as

- Musahib in Jaipur,

- Diwan in Kota and Bundi

- Mukhtyar in Bikaner

- Pradhan in Mewar, Marwar and Jaisalmer

- Bhanjgarh in Salumber

Diwan :

- He often assumed the highest administrative role, especially in the absence of a Pradhan. The Diwan primarily handled revenue collection and financial matters, maintaining records in the Diwan-e-Hazuri office. His consent was also taken in state appointments, promotions and transfers.

Other key officials :

- Mehkma-e-Bakayat : This department operated under the Diwan’s office and was responsible for issuing directives to the officials of parganas regarding revenue rates, collection of arrears, and the funds to be sent to Diwan-e-Hazoori.

- Bakshi : The head of the military department, Bakshi oversaw soldiers’ salaries, supplies, recruitment, and training. As a trusted confidant of the king, Bakshi participated in confidential state deliberations. Bakshi’s subordinates included Naib-Bakshi, Kiledars, and Khabar Navis.

- Khan-Sama : This officer, under the Diwan, held a highly influential position close to the royal family. He was Responsible for procuring and managing state materials.

- Kotwal : Kotwals were appointed in the state capital and larger towns. Their duties included maintaining law and order, regulating prices, monitoring weights and measures, overseeing roads, organizing night patrols, and resolving minor disputes.

- Sikdar : He was similar to Kotwal. His duty was to look after the work related to employment of non-military personnel.

- Khajanchi : Khajanchi managed the state treasury, including receiving and disbursing funds. In Mewar, this position was referred to as Koshpati.

- Dyodhidar : Dyodhidar, literally meaning “gatekeeper,” was stationed at the palace’s entrance halls. Visitors wishing to meet the king required the Dyodhidar’s permission. There were two types of Dyodhidars.

- Ordinary Dyodhidar (for the men’s section)

- Daroga Dyodhidar (for the women’s section).

- Mutsaddi : Mutsaddi was responsible for administering various aspects of the princely states’ administration of Rajasthan.

- Waqia-Navis : Waqia-Navis managed the information transmission department, reporting important events and updates.

- Daroga-e-DakChowki : This officer handled the management of the postal system.

District Administration System

The state was divided into parganas for administrative convenience which was further divided into villages, mandals, and forts. Each pargana had its own officials, known by different titles depending on the region. For instance, in Marwar, these officials were referred to as Hakim and Faujdar. The head of a village was called the Gramika, the head of a mandal was known as the Mandalpati, and the head of a fort was called the Durgadhipati or Talaraksha.

- Amil : The Amil was responsible for implementing land revenue rates and collecting land revenue in the pargana. He was assisted by officials such as Kanungo, Patel, Patwari, and Chaudhary.

- Hakim : The Hakim was the highest-ranking official in the pargana, overseeing both administrative and judicial functions. He was supported by subordinate officials such as the Shikdar, Kanungo, Khajanchi, and Shahne, who worked on a salary or in exchange for grain.

- Faujdar : The Faujdar served as the head of police and military in the pargana. He was responsible for safeguarding the pargana’s boundaries and assisting officials like Amal Guzar, Amin, and Amil in revenue collection. The Thanedars under him were tasked with detecting thieves and robbers. In Marwar, when the Faujdar led campaigns against robbers, it was referred to as ‘Bahar Chadna (बाहर चढ़ना).’

- Ohdedar : In larger parganas, an Ohdedar was also appointed to assist the Hakim in administrative tasks.

- Khufia Navis : The Khufia Navis was responsible for preparing confidential reports about the pargana and sending them to the Diwan.

- Potdar : The Potdar maintained accounts of income and expenditure within the pargana.

Village Administration System

Villages, the smallest administrative units, were known as maujas. Established villages were called Asli, while newly settled ones were termed Dakhili. The Gramika acted as the village head and was responsible for overseeing governance. There were various different names of villages on the basis of population for Eg. in Mewar

- Villages with a higher Rajput population were called ‘Gada’,

- Villages dominated by Bhil and Meena communities were referred to as ‘Gameti’,

- Villages with a majority of merchants or Mahajans were called ‘Patwari’.

The village council (Gram Panchayat) handled justice, disputes, and religious/social activities, recognized by the state. Here are some Officials in Village Administration .

- Patwari: Maintained land records and collected revenue.

- Kanwari: Responsible for protecting crops.

- Dafedar: Kept state accounts.

- Talwati: Measured and weighed the produce.

Military Organization

Divisions of the Military

- Ahadi: The ruler’s army [Recruitment, training, and salaries were managed by the Diwan and Mir Baksh]

- Jamiyat: The feudal lords’ army [handled by the feudal lords]

Two Key Components

- Pyade (Infantry/Foot Soldiers) :

- The infantry formed the largest segment of the Rajput army.

- Ahshama Soldiers – these soldiers equipped with bows, swords, and daggers.

- Sehabandi Soldiers – These were Temporary soldiers hired for tax collection.

- Cavalry (Mounted Soldiers) :

- This included horsemen (घुड़सवार) and camel riders (शुतरसवार), forming the backbone of the Rajput military.

- Bargir – The Soldiers who were provided horses and weapons by the state called Bargir.

- Siledar – The Soldiers who were responsible for arranging their own equipment.

- Classifications of Horsemen:

- Yak Aspa: Possessed one horse.

- Du Aspa: Possessed two horses.

- Sih Aspa: Possessed three horses.

- Nim Aspa: Two soldiers shared one horse.

Feudal System

Rajput rulers divided their vast territories into smaller land grants to their relatives or officials, known as Samants (feudal lords). The feudal system in Rajasthan was unique, built on blood relations and clan loyalty, unlike European feudalism, which emphasized relationships of overlord and vassal. The feudals were responsible for Maintaining law and order, tax collection, and dispensing justice but they lacked the authority to impose capital punishment, mint coins, or establish foreign alliances.

- Succession Fees : A fee charged upon the appointment of a new feudal lord after the previous one’s death. Non-payment could lead to forfeiture of the estate. Jaisalmer was the only princely state in Rajputana exempt from succession fees. It had different names in different states such as

- Talwar Bandhai / Kaid khalsa – In Mewar

- Hukamnama / Peshkashi – Marwar

- Nazrana – In Jaipur

- Peshkashi – In Bikaner

- Rekh (Revenue Standard) : The Rekh was the standard for determining royal taxes collected from Samantas or Jagirdars. In Marwar, Rekh was classified into:

- Patta Rekh: Estimated annual income of the Jagir Which was mentioned in the jagir patta given by the ruler.

- Bhartu Rekh: Amount deposited in the royal treasury based on Patta Rekh.

Classification of Samantas

- Mewar : Three classes of feudal lords

- First Category : Their number was Solah (16) , Also called ‘Umarao’.

- Second Category: number was Battis (32) , also called ‘Sardar’.

- Third Category: they were many in numbers called ‘Gol’.

- Marwar :

- Rajvis: Relatives of the royal family within three generations.

- Sardars: Non-royal family Samantas.

- Ganayats: Those who received jagir due to marriage relations with the royal family.

- Mutsaddi: Officials with Jagirs.

- Kota : Two Categories:

- Desh Samantas: Assigned Jagirs for service.

- Darbar Samantas: Feudal lords of the court.

- Jaipur : Samantas were classified into Barah Kotri (12 groups)

- First Kotri: Close royal relatives called Rajawat.

- Others: Nathawat, Khangarot, Bankawat, etc.

- Thirteenth Kotri was for the Gurjars.

- Bikaner : Three categories

- Ist and IInd – called ‘Aasamidaar chakar pattayat’ these were relatives of Rao Bika.

- IIIrd – These were Sankhala, Bhatis.

- Jaisalmer : Two Categories

- First – Davi Mishal

- Second – Jeevani Mishal

- Bharatpur : Feudal lords were called Solah Kotri Thakurs (16 groups).

Privileges of Feudal Lords

- Tajim : two types

- Feudal lords were honored by the ruler standing up to welcome them.

- The act of placing hands on the lord’s shoulders was called Bah Pasav.

- Seeropav : Refers to gifts like garments or ornaments given to lords.

- Kurb Traditions (Salutations) :

- Hath ka Kurb: The feudal lord touched the ruler’s knees, and the ruler reciprocated with a hand gesture.

- Sir ka Kurb: Special honor allowing specific lords to sit above others.

Features of the Feudal Administrative System :

- Feudal lords inherited land as a birthright, along with defined privileges and responsibilities.

- It was a kinship-based clan system rooted in shared lineage.

- Kings appointed feudal lords to important administrative positions.

- Kings could not make significant administrative, military, or policy decisions without consulting the feudal lords.

- The relationship between kings and feudal lords was not based on a master-servant dynamic. Instead, a code of conduct was observed, where kings addressed feudal lords as Kakaji or Bhaiji, and the feudal lords referred to the king as Bapji.

- Feudal lords’ rise and fall depended on the king. They couldn’t make independent decisions on wars or treaties.

- For the state’s security, feudal lords maintained a certain number of troops, typically on a kinship basis. They considered protecting their ancestral properties a personal responsibility.

- They played a decisive role in choosing the king’s successor and could reject the eldest son if deemed unfit, opting for a more capable heir.

- This system was honor- and duty-based. Kings had to respect the privileges of feudal lords, who, in turn, were obligated to fulfill their duties towards the state and ruler.

Revenue System

Classification of Land : land was classified into various types on the basis of Revenue, Fertility and Irrigation means.

Based on Revenue :

- Khalsa: Land under direct state control; officers handled revenue collection or exemption.

- Bhom: Exempt from taxes; services provided by Bhomiyas during emergencies.

- Jagir: Given to nobles for military or administrative services; required state approval for transfer.

- Sasan: Granted for religious purposes.

- Inam: Tax-free land for state services; not transferable.

- Grass: land given by the ruler in return for military service.

- Bhomiyas: Rajputs given hereditary land for sacrifices in state service.

- Alufati Land: For royal women’s lifetime expenses.

- Doli: Tax-free land donated for religious purposes.

- Doomba: Agricultural land developed by settlers, taxable.

Based on Fertility and Irrigation :

- Beed : Land near rivers.

- Dimdu : Near wells.

- Gormo : Near villages.

- Maal : Black, fertile land.

- Peewal : Irrigated by wells/ponds.

- Barani : Unirrigated land.

- Chahi : Irrigated by canals/rivers.

- Talai : Pond-bed land.

- Hak-bakht : Cultivated land.

- Galt-Hos : Waterlogged land.

- Charanot : Reserved for grazing; under panchayat control.

- Banjar : Non-cultivable land for public use.

- Pasatia: Granted for state services, reverted to the state after service.

Revenue Assessment Systems :

- Batai System: After harvesting the crop, it was shared between state and farmer (⅓ share for the state). Types:

- Khet Batai: Division during harvesting.

- Lank Batai: Division after cutting.

- Raas Batai: Division post-threshing.

- Lata – Kunta: These were the methods to estimate the yield of standing crop for collecting revenue.

- Lata – Share determined after cleaning crops.

- Kunta: Estimated share based on standing crops.

- Beghodi: Revenue per bigha based on fertility.

- Jabti: Cash revenue for cash crops per bigha.

- Mukata: Fixed revenue for each field.

- Dori: Revenue based on measured land.

- Ghughri: Revenue based on production.

- Hal System: Revenue based on land plowed by one plow (15–30 bighas).

- Cash or Bheja: Revenue in cash, termed “Bheja” in eastern Rajasthan.

- Bhint Ki Bhasa: Based on household numbers in Bikaner.

Revenue Officials :

- Diwan: Managed revenue to increase state income and meet expenses.

- Amil: Collected revenue at Pargana level, assisted by Patwari and others.

- Hakim: Oversaw justice, peace, and revenue.

- Sahne: Fixed state’s revenue share.

- Tafedar: Maintained village-level revenue records.

- Sair Daroga: Collected customs duties.

Important Revenue Terms

- Chatund: One-sixth of income given by nobles in Mewar.

- Adasatta: Jaipur’s land records. It contains the details of the land, production etc. of all the mauzas in the parganas of Jaipur state

- Sayar: Common name for Import/Export duty, Custom duty and Chungi Tax in Jaipur.

- Saad System: The Saad system was introduced during British rule in the Mewar region. Under this system, farmers had to pay land revenue, and the state relied on local moneylenders (Mahajans) for assurance of payment. This system led to farmers becoming increasingly dependent on moneylenders, ultimately trapping them in a cycle of debt and exploitation.

Land Revenue Tax System

- Land revenue Rates : The system of land revenue in Rajasthan was based on different methods of collecting a portion of the agricultural produce. Valuable crops were taxed per unit of land, referred to as “Beeghodi.” There was a distinction in tax collection between japti (seized) and raiyati (tenant-owned) lands. Generally, 1/3 or 1/4 of the produce was collected as revenue, but traditionally, in Rajputana, the rate was 1/7 or 1/8. Farmers were also burdened with several additional taxes i.e Udrang, Bhag and Hiranya. After paying all types of revenue, only about 2/5 of the produce remained with the cultivators.

Types of Agricultural Taxes

- Udrang – This tax was 1/6, 1/8, or 1/10 of the produce and was collected from farmers who considered the land their hereditary property.

- Bhag – This was imposed on land where anyone could cultivate, and the state would take a pre-decided portion of the produce. The rate of bhag was much higher than udrang.

- Hiranya – When the state collected its share of revenue in cash instead of produce, it was termed “Hiranya.”

Major Taxs and Lag-Bag

- Dastoor: Illegal levy by revenue staff.

- Nyauta Lag: Tax for nobles’ family events.

- Chavari Lag: Tax during daughters’ weddings.

- Khichdi Lag: Tax during nobles’ visits.

- Baiji Lag: Tax for daughters’ births.

- Sigonti: Tax on cattle sales.

- Jajam Lag: Tax on land sales.

- Kunwarji Ka Ghoda: Tax for prince’s horse training.

- Chudha Lag: Tax for new bangles by noble women.

- Levy: Grain collected by rulers.

- Halma: Labor tax for plowing.

- Malwa: Nobles’ tax for servant expenses.

- Kunwarji Ka Kaleva: Tax for princes’ allowances.

- Kamtha Lag: Tax for fort construction.

- Dan: Tax on inter-state goods.

- Bandoli Ri Lag: Tax during noble weddings.

- Nuta: Tax for noble events or mourning.

- Karj Kharch: Tax for nobles’ family deaths.

- Kagli or Nata: Tax during widows’ remarriage.

Landowners and Farmers:

- Bapidar: Hereditary landowners in Khalsa areas.

- Rayati: Temporary landholders with seasonal leases.

- Pahikasht: Farmers working in other villages.

- Riayati: Privileged farmers with special rights.

- Gewati: Permanent village residents.

FAQ (Previous year questions)

The person responsible for the maintenance, inspection, and security of the royal palaces was called a “Dyodidar.”

This position was hereditary, and the appointed person held the keys to the palaces.

The Dyodidar kept an eye on every visitor in the presence of the ruler and maintained records of those who visited or paid respect to the ruler in his absence. Managing and supervising various security-related tasks of the royal palaces were also part of his duties.

A person appointed to this position was only relieved of their duties if their trustworthiness came into question or they were involved in a dispute. Therefore, the responsibilities of this position were very sensitive.