Static Electricity is a topic in Physics that explains the build-up of electric charge on the surface of objects. It occurs when two materials are rubbed together, causing electrons to transfer from one to another. This phenomenon can be observed in everyday life, such as the spark when touching a doorknob or the attraction of small paper bits to a rubbed comb.

Static Electricity

Have you ever:

- Seen a spark or heard a crackle while removing a synthetic sweater?

- Felt a mild electric shock when touching a car door or an iron bar on a bus?

- Noticed paper strips clinging to a TV screen or a balloon sticking to a wall after rubbing it on your hair?

- Witnessed the spectacular flash of lightning during a thunderstorm?

All these phenomena are caused by static electricity, which results from the accumulation of electric charges on objects. Unlike current electricity, which involves the continuous flow of charges, static electricity deals with charges at rest.

Static Electricity

- Static electricity is the accumulation of electric charge on an object’s surface due to friction, conduction, or induction. Unlike current electricity, where charges flow, static electricity remains stationary until discharged.

- It occurs when electrons (negatively charged particles) move from one material to another. If the material gaining electrons is an insulator or isolated from a conductor, the charge remains in place, creating a buildup of static electricity. When the charge finds a path to flow, it is discharged, converting static electricity into current electricity.

Example:

- When you rub a balloon on your hair, electrons move from your hair to the balloon. Your hair becomes positively charged, and the balloon becomes negatively charged. The attraction between these opposite charges makes the balloon stick to a wall.

- Walking on a Carpet: When a person moves across a carpet, their body strips electrons from the carpet fibers, leaving the carpet positively charged.

- The person accumulates excess electrons. If they touch a conductor (e.g., a metal doorknob), the electrons rapidly discharge, creating a small spark.

- Strands of hair may stand on end due to repulsion between like charges.

- Spark or Crackle While Removing a Synthetic Sweater

- As you take off a synthetic sweater, friction between the fabric and your body transfers electrons.

- This causes charge buildup and, when discharged suddenly, it creates a spark or a crackling sound.

- Mild Shock from a Car Door or Bus Iron Bar

- When you walk on a carpet or get out of a car seat, your body collects excess electrons.

- Touching a metal object (like a car door or bus bar) instantly discharges the static electricity, giving you a small shock.

- Paper Strips Clinging to a TV Screen or Balloon Sticking to a Wall

- The TV screen or balloon gains static charge through friction.

- Lightweight objects like paper or hair are attracted to it due to electrostatic forces.

- Hair Standing Up After Removing a Woolen Cap

- The cap and hair rub against each other, transferring electrons.

- Since each hair strand gets the same charge, they repel each other, making your hair stand up.

- Lightning Strikes:

- In storm clouds, small hail particles collide, transferring charge.

- The cloud becomes electrically polarized, with a charge difference between the cloud and the ground.

- When the charge buildup exceeds the insulating ability of the air, a sudden discharge occurs, producing lightning.

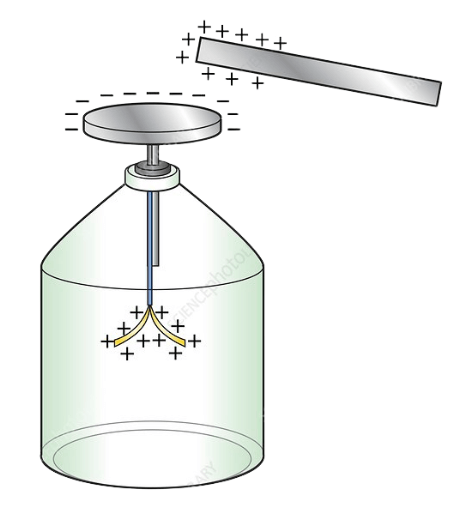

Gold-Leaf Electroscope: Detecting Electric Charge

- An electroscope is a simple device used to detect and measure electric charge on an object. The gold-leaf electroscope consists of a metal rod connected to two thin gold leaves enclosed in a glass container.

When a charged object touches the metal knob, charge flows down to the gold leaves, causing them to diverge due to electrostatic repulsion. The degree of divergence is an indicator of the amount of charge on the electroscope.

How It Works

- When a charged object touches the ball end, charge transfers to the leaves, making them repel.

- The greater the charge, the wider the leaf separation.

- The effect is similar to two ironed paper strips repelling each other due to like charges.

Van de Graaff Generator Experiment:

- This device collects electric charge on a metallic sphere, demonstrating how static charge builds up and redistributes itself across a person’s body, making their hair stand on end.

Triboelectric effect:

- When different materials come into contact, electrons can transfer between them. The material losing electrons becomes positively charged, while the material gaining electrons becomes negatively charged. This process is known as the triboelectric effect.

- Triboelectric Series (Charge Gaining and Losing Materials)

- Materials that become positive (Lose electrons): Glass, Wool, Hair, Paper

- Materials that become negative (Gain electrons): Plastic, Rubber, Balloon, Silk

Methods of Charge Transfer

(a) Charging by Friction (Rubbing)

- When two different materials are rubbed together, electrons transfer from one material to the other.

- The object losing electrons becomes positively charged, and the object gaining electrons becomes negatively charged.

- Examples:

- Rubbing a glass rod with silk → The glass rod becomes positive and silk becomes negative.

- Rubbing a plastic rod with fur → The plastic rod becomes negative, and the fur becomes positive.

(b) Charging by Contact (Conduction)

- A charged object can transfer its charge to another object by direct contact.

- This happens because electrons move between the objects until they reach equilibrium.

- Example:

- A positively charged rod touching a neutral metal sphere transfers some of its charge to the sphere, making it positively charged.

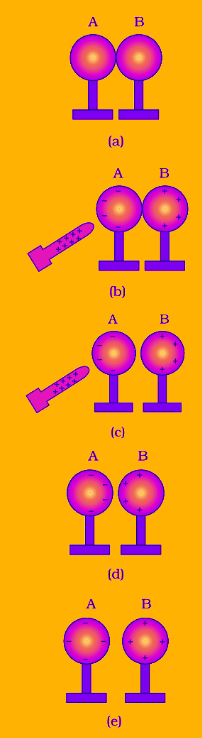

(c) Charging by Induction (Without Contact)

- Charging by induction occurs when a charged object is brought near a neutral conductor, causing a redistribution of charges without direct contact.

- This process is different from charging by contact, where charge is transferred by physical touch.

Example:

- Bringing a negatively charged rod near a metal object repels electrons in the metal, leaving one side positively charged and the other negatively charged.

Steps in Charging by Induction

- Redistribution of Charges:

- Bring a positively charged rod close to two neutral metal spheres A and B, which are touching each other.

- Free electrons in the spheres are attracted toward the positively charged rod, accumulating on the side of sphere A closest to the rod.

- This leaves sphere B with an excess of positive charge at its farthest side.

- Separation of Spheres:

- While keeping the charged rod near sphere A, separate spheres A and B slightly.

- Now, sphere A has an excess of negative charge, while sphere B has an excess of positive charge.

- Removing the Rod:

- If we now remove the charged rod, the charges remain on the spheres and redistribute over their surfaces.

- The spheres are now oppositely charged without any direct contact with the charged rod.

Thus, charging by induction allows an object to be charged without losing any charge from the inducing object.

Why Does an Electrified Rod Attract Light Objects?

- When a charged rod is brought near a neutral light object (e.g., bits of paper or a pith ball), it induces opposite charge on the object’s near side.

- Induced opposite charge → Strong attraction

- Induced like charge → Weak repulsion (farther away)

- Since attraction is stronger than repulsion (due to distance differences), the light object moves toward the rod.

Useful Applications of Static Electricity:

- Air Filters & Dust Removal: Electrostatic filters trap airborne particles using opposite charges.

- Xerography (Photocopying): A charged drum attracts toner particles to create images.

Potential Hazards:

- Electronics Damage: Static discharge can harm sensitive electronic components.

- Fire Risk in Fuel Pipelines: Friction from liquid movement can generate static electricity. If discharged as a spark near flammable vapors, it may cause an explosion.

Conductors and Insulators

Materials can be classified as conductors and insulators based on their ability to allow electricity to pass through them.

Conductors

- Definition: Materials that allow free movement of electric charge.

- Reason: Conductors have loosely bound electrons that move easily.

- Effect on Static Electricity: Charges spread and do not remain stationary, so static electricity does not build up.

- Examples:

- Metals (Copper, Silver, Gold, Aluminum)

- Graphite

- Human Body (which is why we feel shocks from static discharge!)

Experimental Demonstration of Conductors:

- A metal rod rubbed with wool does not hold a charge when held in hand.

- Since both the metal rod and the human body are conductors, the charge immediately leaks into the ground.

- If the metal rod is held with an insulating handle (wood or plastic), it retains charge, proving that direct contact with a conductor allows charge to flow away.

Insulators

- Definition: Materials that do not allow charge to move freely.

- Reason: Their electrons are tightly bound, preventing charge flow.

- Effect on Static Electricity: Charge stays localized, allowing static electricity to build up

- Examples:

- Plastic, Rubber, Glass, Wood, Dry Air

Experimental Demonstration of Insulators:

- A plastic comb rubbed on dry hair becomes charged and can attract small paper pieces.

- A metal spoon rubbed in the same way does not get charged, because metals allow charge to escape through our body into the ground.

- This explains why synthetic clothes spark in dry weather—the charge remains trapped on the insulating fabric instead of flowing away.

- A metal wire connected between a charged plastic rod and a neutral pith ball transfers charge to the pith ball, making it charged.

- If nylon thread or rubber is used instead of the metal wire, no charge transfer occurs, proving that charge does not flow through insulators.

Differences Between Conductors and Insulators

| Property | Conductors | Insulators |

| Definition | Materials that allow electric charges (electrons) to flow easily. | Materials that resist the flow of electric charges. |

| Electron Movement | Electrons are free to move. | Electrons are tightly bound to atoms, restricting movement. |

| Effect of Static Electricity | Cannot hold static charge easily, as charges move away. | Can accumulate static charge due to poor conductivity. |

| Electrical Resistance | Low resistance (allows current to flow). | High resistance (blocks current flow). |

| Examples | Metals like copper, silver, aluminum, gold, iron, and water with dissolved salts. | Rubber, plastic, wood, glass, dry air, ceramics. |

| Use in Circuits | Used to make wires, connectors, and electrical components. | Used to coat wires (as insulation) and prevent shocks. |

| Thermal Conductivity | Good heat conductors (e.g., metals). | Poor heat conductors (used for thermal insulation). |

| Application Examples | Electrical wiring, cooking utensils, power transmission lines. | Insulating handles of tools, rubber gloves, plastic coatings. |

Earthing (Grounding)

A Safety Measure in Electrical Systems

- Earthing (grounding) is the process of transferring excess charge from a charged object to the Earth.

- It prevents electric shocks and protects electrical appliances from damage.

How Earthing Works:

- A thick metal plate is buried deep into the ground.

- A metallic wire connects this plate to buildings and electrical appliances.

- If an electrical fault occurs (e.g., a live wire touches a metal body), charge flows safely into the ground instead of passing through a human body.

Examples of Earthing in Daily Life:

- Electric appliances (e.g., refrigerators, TVs, washing machines) are earthed to prevent shocks.

- Power lines in buildings include a third wire called the earth wire to carry away excess charge.

Semiconductors: The Middle Ground Between Conductors and Insulators

- Semiconductors are materials that have electrical conductivity between that of conductors and insulators. Their ability to conduct electricity can be controlled and modified using temperature, impurities (doping), or an electric field.

- Example: Silicon (Si), Germanium (Ge), Gallium Arsenide (GaAs).

- Doping: Adding small amounts of impurities (dopants) to a semiconductor changes its electrical properties.

- Types of Doping:

- n-type (extra electrons, e.g., phosphorus-doped silicon).

- p-type (extra holes, e.g., boron-doped silicon).

- Types of Doping:

- Temperature Dependence:

- Unlike metals, semiconductors become better conductors at higher temperatures.

- This is why electronic devices need cooling systems.

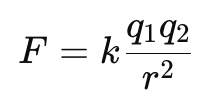

Coulomb’s Law

Electric charges exert forces on each other. Have you ever noticed how:

- Two charged balloons repel each other?

- A rubbed plastic comb attracts paper bits?

All these effects occur due to electrostatic forces between charges. Coulomb’s Law, formulated by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb in 1785, quantifies this force between two point charges.

Statement: “The force between two point charges is directly proportional to the product of their charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.”

Mathematically,

- where:

- F = Electrostatic force between the charges (in Newtons, N)

- q1 and q2 = Magnitudes of the two charges (in Coulombs, C)

- r = Distance between the two charges (in meters, m)

- k = Coulomb’s constant, 9×109 N·m²/C²

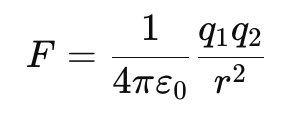

Alternate Form Using Permittivity (ε₀):

where ε₀ = 8.854 × 10⁻¹² C²/N·m² (permittivity of free space).

Nature of Electrostatic Force

- The force follows the inverse-square law, meaning if the distance doubles, the force reduces to one-fourth.

- Direction of Force: The force acts along the line joining the two charges. It is repulsive if both charges are the same (positive or negative) and attractive if they are opposite.

- Conservative Force: The electrostatic force is conservative, meaning the work done in moving a charge depends only on its initial and final positions.

- Superposition Principle: In systems with multiple charges, the net force on a charge is the vector sum of the forces due to all other charges.

- Applies to Point Charges: Coulomb’s Law is most accurate for point charges or spherically symmetric objects. Irregularly shaped objects require more complex calculations.

- Works in Vacuum & Medium: The force is stronger in a vacuum and decreases in a medium based on the dielectric constant.

- Comparison with Gravity: Like gravity, Coulomb’s Law follows the inverse square law, but gravity is always attractive, while electrostatic forces can be both attractive and repulsive.

Coulomb used a torsion balance to measure the force between two charged metallic spheres.

- He varied the distance between the spheres and measured the force for different separations.

- He also varied the charges on the spheres and found how force changed.

- Through experiments, he found the inverse square relationship and the direct proportionality to charge product.

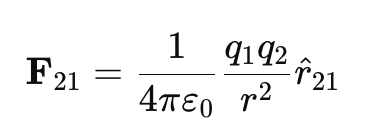

Vector Form of Coulomb’s Law:

Since force is a vector quantity, it has both magnitude and direction. The vector form of Coulomb’s law is:

where:

- F21 is the force on charge q2 due to charge q1.

- r̂21 is the unit vector pointing from q1 to q2.

- If q1 and q2 are like charges, the force vector points away (repulsion).

- If q1 and q2 are unlike charges, the force vector points toward the other charge (attraction).

- Coulomb’s Law follows Newton’s Third Law, meaning:

F12 = −F21

(The force exerted by q1 on q2 is equal and opposite to the force exerted by q2 on q1).

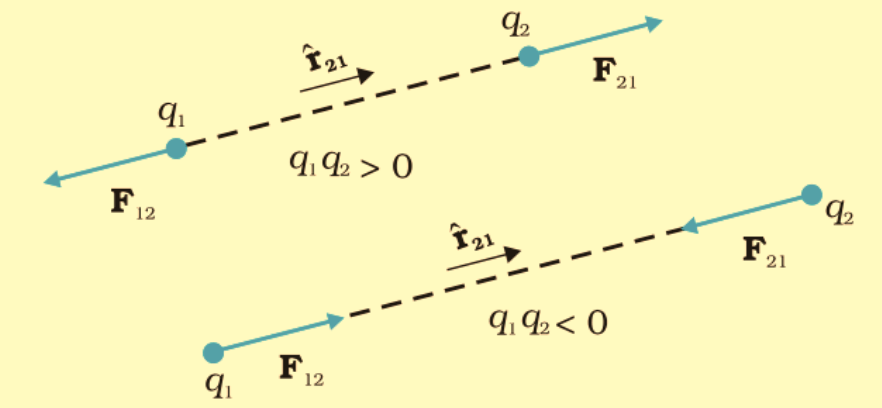

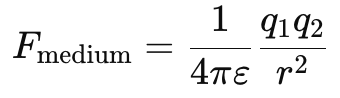

Coulomb’s Law in a Medium (Permittivity Effect)

- Coulomb’s Law applies perfectly in vacuum.

- In a medium, the force is weaker due to the presence of molecular dipoles in the material.

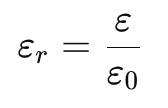

- The modified Coulomb’s Law is:

where ε is the permittivity of the medium.

- The relative permittivity (or dielectric constant) is:

- The force in a medium is weaker than in vacuum by a factor of εr:

Example:

- For water, εr=80, meaning Coulomb’s force is 80 times weaker in water than in vacuum.

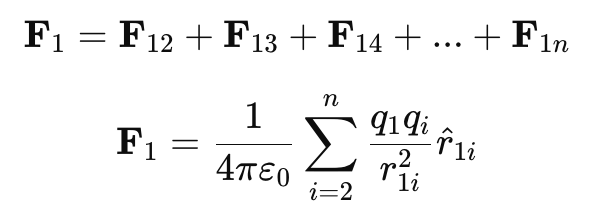

The Superposition Principle

Forces Between Multiple Charges:

- The net electrostatic force on a charge due to multiple other charges is the vector sum of the forces due to each charge, taken one at a time.

- The presence of additional charges does not affect the force between any two individual charges.

- This means electrostatic forces obey the law of vector addition, similar to mechanical forces.

- Mathematically, for a system of n charges q1,q2,q3,….,qn, the net force on charge q1 due to all other charges is:

where:

- F1 = Total force on charge q1

- F1i = Force on q1 due to qi

- r1i = Distance between charges q1 and qi

- r̂1i = Unit vector from q1 to qi

- ε0 = Permittivity of free space

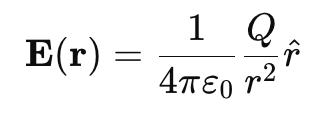

Electric Field

Understanding the Force in Space

- The electric field is a region around a charge where another charge experiences a force.

- If we place a charge q near another charge Q, it experiences a Coulomb force.

- But what exists at that point when qq is absent?

- Scientists introduced the concept of an electric field, which represents the influence of charge Q in space.

Definition: The electric field at a point is the force experienced by a unit positive charge placed at that point.

The electric field E at a distance r from a point charge Q in vacuum is:

where:

- E = Electric field (N/C)

- Q = Source charge (C)

- r = Distance from charge QQ (m)

- r̂ = Unit vector from the charge to the point of observation

- ε0 = Permittivity of free space (8.854 × 10⁻¹² C²/N·m²)

Force Experienced by a Charge in an Electric Field

- When a charge q is placed in an electric field E, it experiences an electrostatic force given by:

F = qE

- If q is positive, the force is in the direction of the electric field.

- If q is negative, the force is opposite to the direction of the electric field.

Unit of Electric Field:

1 N/C=1 V/m

(N/C = Newton per Coulomb, V/m = Volt per meter)

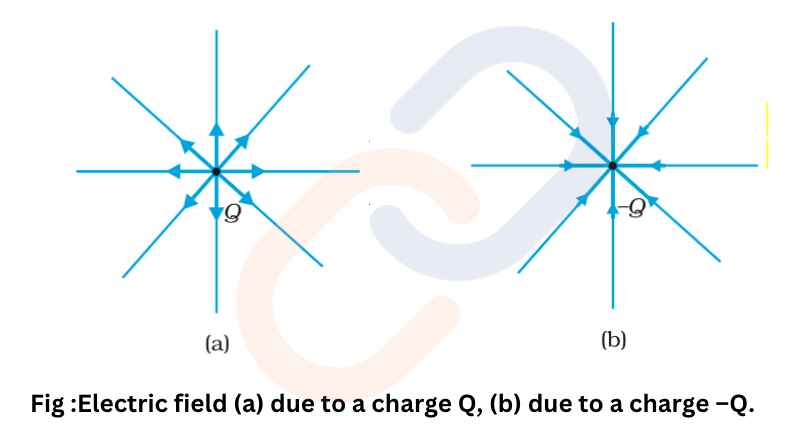

Direction of Electric Field

- For a positive charge Q: The electric field radiates outward from the charge.

- For a negative charge Q: The electric field points inward toward the charge.

The electric field is radial—outward for positive charges, inward for negative charges.The electric field around a point charge is radially symmetric.

At equal distances from a charge, the field strength is constant in all directions.

Properties of the Electric Field

- Vector Field: The electric field has both magnitude and direction.

- Depends on Position: E changes with distance from Q.

- Superposition Principle Applies:

- If multiple charges exist, the total electric field is the vector sum of individual fields.

Physical Significance of Electric Field

- Coulomb’s Law directly calculates force, but it does not explain how the force acts across space.

- The field concept describes the influence of charge without needing another charge.

- It helps explain force propagation in time-dependent scenarios (like electromagnetic waves).

Electric Field Lines: A Pictorial Representation of Electric Fields

- The concept of electric field lines was introduced by Michael Faraday.

- He originally called them “lines of force”, but today we use the more precise term “field lines”.

- Electric field lines are imaginary lines drawn to represent the direction of the electric field at different points in space.

- At each point, the tangent to the field line gives the direction of the electric field vector at that location.

- The density of field lines indicates the strength of the electric field.

- More crowded field lines = Stronger field

- Widely spaced field lines = Weaker field

- The electric field follows the inverse-square law. This means that as you move farther from the charge, the field gets weaker, and the field lines become less dense.

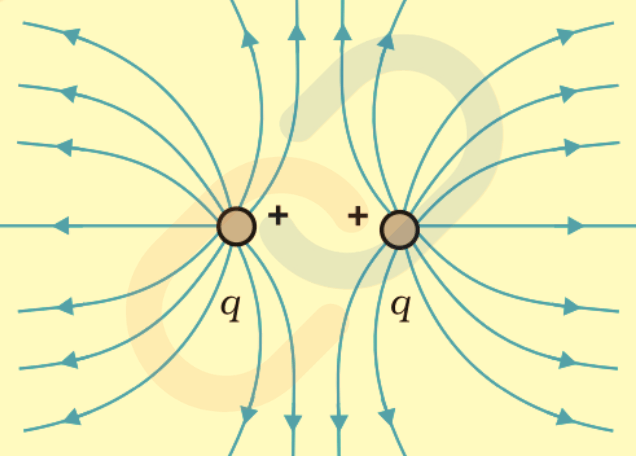

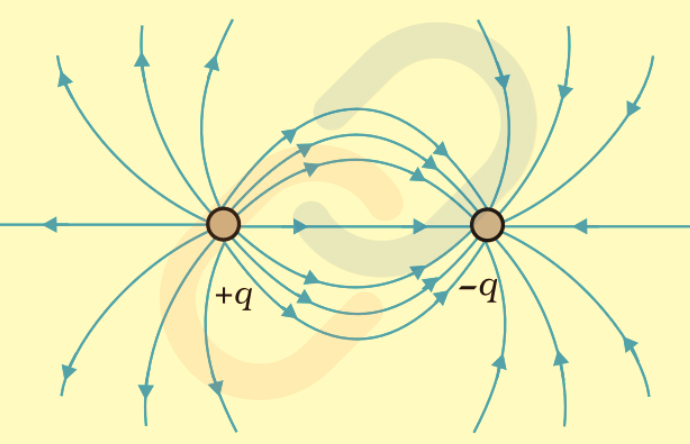

Field Lines Around Charge Configurations

- Single Charge: Field lines are radial—outward for a positive charge, inward for a negative charge.

- Two Like Charges (+q, +q): Field lines repel each other, showing mutual repulsion.

- Dipole (+q, -q): Field lines curve between the charges, illustrating attraction.

Properties of Electric Field Lines

- Originate from positive charges and terminate at negative charges (or extend to infinity in case of isolated charges).

- Do not break or suddenly stop—they form continuous curves.

- Never intersect—otherwise, the field at the intersection point would have two different directions, which is impossible.

- Do not form closed loops—unlike magnetic field lines, electric field lines always have a beginning and an end.

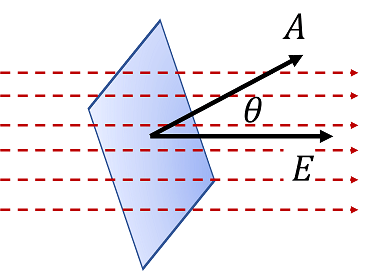

Electric Flux (ΦE)

Electric flux is the total number of electric field lines passing through a given surface.

Mathematical Expression:

ΦE = E⋅A = EAcosθ

- Where:

- E = Electric field intensity (N/C)

- A = Area of the surface (m²)

- θ = Angle between the electric field and the normal to the surface

- If θ=0 (Field perpendicular to the surface) → Maximum flux (ΦE=EA)

- If θ=90∘ (Field parallel to the surface) → Zero flux (ΦE=0)

Gauss’s Law

“The total electric flux through a closed surface is proportional to the total charge enclosed by that surface.”

∮E⋅dA = Qenclosed/ε0

Where:

- ∮E⋅dA= Total electric flux

- Qenclosed = Net charge inside the surface

- ε0 = Permittivity of free space (8.85×10-12 C²/N·m²)

- If no charge is inside the surface, the net flux is zero.

- If charge is enclosed, the flux is nonzero and depends on the total charge.

Comparison between Gravitational and Electrostatic forces

Borth are One of the four fundamental forces of nature.

| Parameter | Gravitational Force | Electrostatic Force |

| Nature | Always attractive | Can be attractive or repulsive |

| Formula | ||

| Proportionality | Directly proportional to the product of masses | Directly proportional to the product of charges |

| Constant Used | Gravitational constant G=6.674×10-11 Nm²/kg² | Coulomb’s constant k=9×109 Nm²/C² |

| Strength | Extremely weak (Much weaker than electrostatic force) | Very strong (around 1036 times stronger than gravity) |

| Range | Infinite | Infinite |

| Medium Dependence | Does not depend on the medium | Depends on the medium (e.g., weaker in water than in vacuum) |

| Shielding Effect | Cannot be shielded | Can be shielded using a conductor or Faraday cage |

| Example | Keeps planets in orbit, responsible for weight | Causes attraction/repulsion in charged objects |

Till now, we studied electric charges at rest (static electricity). However, when these charges begin to move, they create electric current—a fundamental concept in electricity.